The art of dowsing for water and minerals has been practised for the past 400 years, and now all classes of society have representatives among the dowsers; whilst those who avail themselves of their art are found in varying grades, from the agent of King Edward's estates, through the ranks of England's highest nobility, down to the tenant farmer.

Scoffers Silenced

This scientifically unrecognised faculty lends itself with almost fatal ease to ridicule.

The spectacle of the stooping, confident man, bent twig or watch-spring, nosing the earth in search of the waters beneath its crust, is certainly one at which the non-believer must not be grudged his smile; but the statistics Professor Barratt has gathered show that the dowser has the laugh in the end.

His long array of attested successes largely preponderates over his comparatively few failures; and, when he promises water in any indicated spot, in nine cases of ten water will be found.

So sure are the dowsers of their faculty that sometimes - like the late John Mullins, who was one of the most reliable dowsers

in Great Britain - they agree on the terms "no water no pay" and themselves sink the wells on the self-indicated localities on that understanding.

Ordinary folk may be reassured when they learn that such illustrious persons as the following have employed dowsers to discover water on their estates : - The agent of King Edward's estate, the agent of Earl of Jersey's, the agent of Earl Beauchamp's, the agent of Duke of Devonshire's, and others of the nobility; Col. Waring, M.P.; Mr. Money Wigram, M.P.; Sir W. Wedderburn, M.P.; Beamish & Crawford, Limited; Merchant Venturer's Society; Bursar Trinity College, Cambridge; various brewing and business firms; and the Union, Mortgage, and Agency Company of Australia.

These and many others testify to the success which followed on putting the dowser's findings to the practical test of boring.

These cases are but a few of hundreds of authenticated examples which can be examined in Professor Barratt's published report; but they are sufficient to show, that men of rank, learning, and business reputation are not slow to avail themselves of a good thing.

How the Dowser Works

Usually the dowser is a Y-shaped rod or twig cut from hedge or tree, one of whose prongs is grasped in each hand.

The kind of wood matters not at all, nor does it make the slightest difference how it is held.

Some dowsers grasp the ends firmly in the hands, with the point turned down; others with the point up, or horizontally, and perhaps held between fingers and thumbs.

Others, again, use a watch spring, which is quite as satisfactory; and in one instance at least the dowser has no aid of the kind at all, but prospects his ground with arms at side and extended palms.

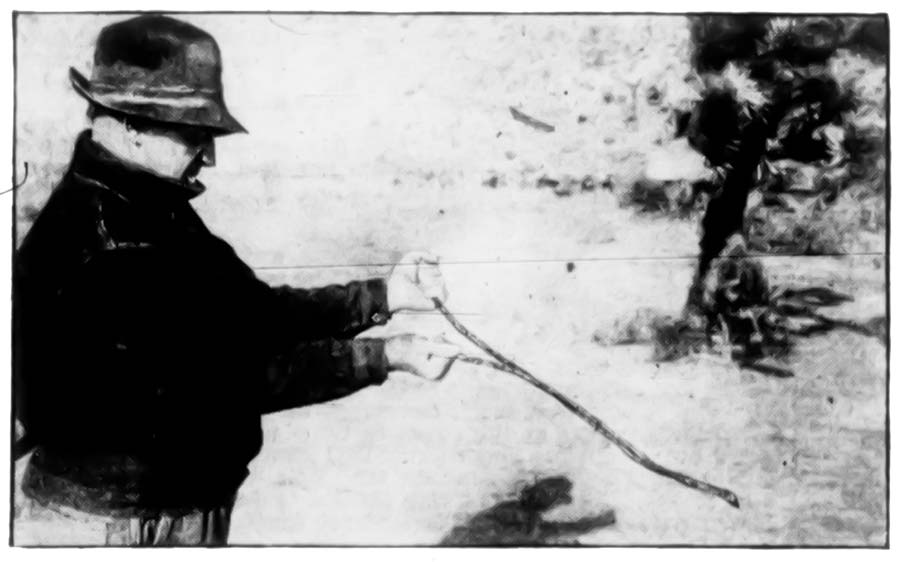

With his forked twig held before him, and elbows firmly pressed to his side, the dowser walks over the ground where it is desired to find water, and directly upon reaching the locality of a spring the rod turns in his hand.

This proceeding has been gone through thousands of times; the recorded successes are numberless; and any idea that trickery is at work may safely be dismissed.

In many cases the tests precluded that; and, apart from these, the lifelong reputation and standing of especially the amateur dowsers point in quite an other direction.

Among the amateurs are clergymen, judges, naval and military officers, ladies, men of business, and children.

They are well known, and their names and addresses are given in Professor Barratt's monograph.

The professional dowser, on the other hand, whose livelihood is earned by the exercise of his faculty, may be

deemed an object whom it is only prudent to regard with watchfulness.

Nevertheless most of these men bear the best of reputations, and few of them have had their characters assailed.

Remarkable Cases

There is such a mass of evidence that it will be possible to give only that of one or two witnessees.

These, however, shall be those of whose bona fides there can be no question.

The most successful professional dowser of the last few decades was the late John Mullins.

His locations of subterranean water were proved in most instances to be correct, and his failures were comparatively few.

The first case is referred to by Professor Barratt, under the heading of 'The Horsham Experiments', and is

quoted in his own words:

The owner of an estate near Horsham, in Sussex, Mr. Henry Harben (now Sir Henry Harben) found a scarcity of water on his property.

He called in the aid of an experienced wellsinker, and had a well sunk some 90 ft. deep, but got little water.

Some 200 yards off, and at the lowest part of the estate, another well was sunk under the advice of another wellsinker.

At some 66 ft. down a small, spring was met, but so small that the supply was quite insufficient.

Having spent a considerable sum uselessly in sinking these two wells, Mr. Harben determined to obtain from London the highest engineering and geological advice.

His position as one of the directors of the New River Company, and his ample means, rendered this comparatively easy.

Under such advice another well was sank to nearly. 300 ft., with, however, little result as regards water.

Tunnels were then driven in various directions! and finally after £1,000 had been spent on this last attempt, made under the best scientific advice and with the most modern and approved engineering methods, the well was abandoned.

Ultimately Mr. Harben was induced to send for the dowser, Mr. J. Mullins, of whom he had beard, and whom he had refused to employ before sinking the last well, as he utterly disbelieved in him.

Mullins came some time in 1893; and, to prevent his gaining any local information, Mr. Harben met him at the railway station and drove him to his estate, Varnham Lodge, some four miles off.

Mullins said it was his first visit to that part of Sussex, and there is no reason to think otherwise.

On arriving Mullins traversed the estate, and said there was no water where the first and last wells were situated, unless an immense depth were bored.

As he came near well the second he was narrowly observed.

Mr. Harden and the wellsinker alone knew the exact direction of the streamlet of water which entered this well.

No hint of any kind was given to Mullins.

Suddenly the rod turned - "There is a small stream here," he said, "flowing in this direction".

This was absolutely correct, I am informed; Mullins indicated the exact direction the streamlet was known to enter the well.

The depth, he said, was between 50 and 60 feet, the actual depth wass 96 ft.

Dissatisfied with this supply, Mullins said he would try higher round.

Mr. Harben tried to dissuade him, as that part had been examined and rejected by the scientific experts. "Never mind," said Mulling "I am going to try it".

At the top of the hill the rod turned vigorously, and the spot was marked; 30 ft. farther on (absolutely on the crest of the hill)

it turned again.

"Call this No. 1," said Mullins; 20 ft. further it turned again. "Call this No. 2" said Mullins.

Mr. Harben then remarked that water doubtless existed every where at a certain depth beneath the hill.

Mullins carefully fried and said, "No, 1 and 2 are independent springs. There is no water between them; but you will find plenty of water at either of these places at 12 ft.-or 15 ft. deep."

Mullins was then taken across the road to find a well for the supply of some cottages on the estate, about 250 ft. distant from these last springs, he found a place where, he said, water would he obtained at about. 40 ft.

A well was dug, and at 35 ft. a good spring was found.

Another place 75 ft. from No. 2 spring, and some little distance from the cottages, was indicated, and on sinking water was found in sufficient quantity for the requirements of the cottages.

The spots marked by Mullins No. 1 and 2 on the crest of the hill were then dug.

Soon a hard lime stone was struck; and, after blasting and sinking at each spot to a depth of 12 ft., a copious supply of excellent water was suddenly met with.

At No. 3 a good spring was also found at 10 ft.

Much to Mr. Barbell's surprise, Mullins had proved right in each case.

Mr. Harben, fortunately for our enquiry, then resolved to go to the expense of testing Mullins's assertion that no water would

be found between wells E and F, but that both were independent springs.

By means of a powerful pump he had one of the wells pumped nearly dry; the water level in the other was unaffected.

To leave room for no doubt, however, Mr. Harben further tested Mullins's statement by tunneling through the solid rock the intervening 20 ft. from the bottom of well E to the bottom of well F; and lie assures me from his own personal observation, corroborated by the overseer, whom I saw, that no water was found between the two

wells, the intermediate rock being dry.

Another Illustration

The next case is furnished by Sir Welby Gregory, Bart., formerly M.P. of Dentou Manor, Grantham, who states that he employed Mullins to find water for a new country house he was building.

After testing the grounds Mullins fixed on two spots, A and B, about 30 yards apart, where he said water would he found; from 20 to 30 feet at A, and from 30 to 40 feet at B.

A neighbouring hill, which lie thought likely to yield a better supply, was traversed, but no indications of water

were given.

Subsequently Sir W. Gregory consulted an eminent civil engineer, who stated, from his geological knowledge of the country,

that the hill was the best place to bore for water, but that none would be found at the places indicated in the grounds, A and B, at a less depth than 120 to 130 feet.

This opinion was confirmed by another geological authority.

However, Sir Welby decided to sink on both the lines indicated.

At A water was found at 20 ft.; at B, as stated by Mullins, a much larger supply at 28 ft.

Between these two, said Mullins, there was no water.

Sir Welby sank a shaft midway and went down 10 to 12 feet deeper than the deepest well, but, although the formation appeared precisely similar, found no water, and neither well was affected by the trial shaft.

Further Experiences

Mullins was also employed by Mr. F. T. Mott, F.R.G.S., to find water on his estate of Charnwood Forest.

The formation was metamorphic slate.

Previously several wells had been sunk without finding water.

In one case they had bored 100 ft. without success.

Mullins searched with the rod, and certain spots were marked.

"Anywhere above that line you will find water at about 30 ft." Mullins said.

At 28 ft. it was reached, and at 31 ft. a constant supply has been obtained.

In the last Journal of the Society for Psychical Research are interesting letters from Mr Wedderburn Maxwell, of Glenlair, N.B., to Sir Oliver Lodge, giving his own experiences in the use of the dowsing rod, with which he has been very successful.

The major says of his first attempt with, the rod : "I had no idea till the wire began to be drawn in my hands towards the spot, and then to twist violently and go straight down, that there was water; but now I can, from practice, blindfolded, and pushed from behind by any one, go about till the wire tells me water is near, and then I can find the spot by attraction."

The Mystery of it

Almost all dowsers - and the professional ones are not usually men of education - ascribe their power to a susceptibility to electrical currents which, they allege, travel along the surface of water, affecting the dowser when he is over them, the motion

of the rod being merely the pulse of the current.

They also assert that when glass insulators intervene between them and the current the rod will not turn, but this idea has been proved groundless through the tests made by Professor Barratt.

Professor Lochman and Monrad, of the University of Christiania, are both convinced of the reality of this phenomenon, and believe it to be of a physiological nature, but can give no further explanation.

Professor Lochman, a distinguished physiologist, was at first sceptical upon the whole question, but had been overcome by the discovery that he himself could successfully use the rod, though of its rationale he was unable to give an account.

Many of the dowsers state that when they are over the locale of a spring they experience certain physiological disturbances. Occasionally the sensation is in the limbs, sometimes it is in the epigastric region.

One dowser, upon coming over a spring, was subject to such a severe nervous affection that he took some hours to recover.

Professor Barratt cannot say much explanation of the faculty, but his methods of research and his conclusions are suggestive and instructive.

The motion of the rod is due, he thinks, "to a latent prior intention and unconscious muscular action;" but that does not solve the mystery of the faculty which enables the dowser with such success to indicate the course of subterraneous water.

The movement of the rod is merely the indicator of a disturbance in the physical region, which it magnifies sufficiently to conduct to from the subconscious to the conscious levels, which otherwise it would seldom reach; but the cause behind the

disturbance in the human medium, is still unknown.

That it does exist, Professor Barratt is satisfied.

So are Mr. J. D. Enys, F.G.S., President of the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall; Dr. R. Raymond, secretary of the American Institute of Mining Engineers; Dr. Lander Brunton, F.R.S., Mr. Leeson Prince, F.R.A.S., and many other persons of culture and intellectual attainments.

Why Doubt ?

There is, after all, no reason why we should be incredulous.

As Dr. Brunton shrewdly points out, "if we are told that a caravan was crossing a desert, when all at once the thirsty camels started off quickly, and at a distance of a mile or more water was found, we look upon the occurrence as natural; but when we hear that a man is able to discover water many feet below the ground on which he stands, we are apt at first to scout the idea as ridiculous."

Nature furnishes many examples of the super sensitiveness to certain influences of some branches of the lower animal kingdom and of some individuals of the higher.

"Professor Milne states that pheasants were kept at Tokio to observe their behavior at the time of earthquakes, with the result that he found they gave him a few seconds warning of shocks of local origin by screaming."

The present writer was told by her brother of a lady in New Zealand who was similarly sensitive to the approaching earth tremors.

She always knew a few seconds beforehand of their coming, and would get out of the house before the vibrations were apparent to the rest of the household.

There may be something analogous to this in the extreme sensitiveness of the dowser to currents of water.

"He seemed to be following a sensation, which is what he professes to do, and he looked very like a dog following the traces of a rabbit over the grass."

This is the account of a witness of the procedure of a dowser well known in England, a man well born and well educated.

According to the conception of the average man - certainly according to the average unscientific dowser - the earth is veined with a network of running springs, which form an underground system some what comparable with the arterial systerm of the body.

To a limited extent the simile may hold good, but in a much less degree than the dowser thinks, says the hydrogeologist.

This gentleman will have none of the dowser.

He considers him an imposter, or, at least, self-deceived.

With him it is a question of evidence, too, but under the supervision of experts; and of these, even in England, says Mr. C. E. De Rance, F.G.S., &c., there are not more than 20.

"Underground water," writes Mr. De Rance, "travels in sheets, and not lines; and though underground 'channels' or 'courses' occur in limestones and impure limestones - like the chalk - occasionally, they are wholly absent in other rocks; though, "of course, these throw lines of springs, where the flow of water is intercepted by faults, throwing in some impermeable material, forming a watertight barrier."

That is a matter for the relatively few experts to decide, but the fact of the dowser's widespread and continuous suecess remains to be accounted for.

It can not be met by the doctrine of chance.

In a paper read before, the American Institute of Mining Engineers Dr. Raymond, the secretary of that important institution, after considerable investigation, arrives at this conclusion "That there is a residuum of scientific value, after making all necessary deductions for exaggeration, self-deception, and fraud," in the use of the divining rod for finding springs and deposits of ore.

That this residuum is very large is shown on the testimony of various well-known and respected gentlemen, who never dream of sinking wells before they have the assistance of the dowser in locating a suitable spot.

It should be said in conclusion that the whole of this article is based upon or extracted from Professor Burratt's admirable monograph, which, unfortunately, is not available to the public.

By Impartial

Adelaide Observer, 5 September 1903